There’s no universal way to irrigate fields with different soil, crop size, or crop types. Any location’s best system provides adequate irrigation without water waste, is easy for the farmer to understand and use, and is reliable and easy to fix if something goes wrong.

Irrigation

Many irrigation schemes around the world will never recover their costs. Beginner farmers should start small and cheap to gain knowledge and experience before investing heavily.

Choosing a location

In addition to soil fertility, depth, and location, consider the following:

- Nearby water makes irrigation easier.

- A gently sloping area is best for surface irrigation. This makes building channels, beds, etc. faster and easier.

- Make sure the location has adequate subsurface drainage. Without proper drainage, irrigation projects have ruined large areas of good farmland.

In hot, evaporative climates, water rises in the soil and evaporates. Salt deposits in the topsoil can inhibit plant growth. Only a net downward movement of water can remove soil salts. In low-drainage areas, adding water will make the soil unusable for farming.

Hand-watering

The watering can and hosepipe method evenly distributes water in small basins and beds. If the crops are far apart, place a small basin around each plant. Wide-area manual watering is inefficient and time-consuming.

Flood irrigation

Flood or surface irrigation systems are cheap and easy to build, but sandy soil requires more water.

Beds/basins

A basin is a flat area surrounded by a bank to hold water. Leveling the area ensures uniform water distribution. Before planting, filling the basin with water helps ensure its level. No area should be deeper or shallower than necessary due to water distribution.

Furrows

Tractors, ploughing equipment, or oxen can prepare ridge-and-furrow quickly. Row irrigation on a gently sloping plot saves time on field preparation.

Water flows downhill into a furrow. Controlling water flow prevents furrow overflow.

During irrigation, water seeps down and sideways into rows of crops planted along ridges. Furrow spacing is crop-dependent.

Surface irrigation basins are limited to 50 m² (5 m wide by 10 m long) and furrows to 100 m for good water distribution.

Sprinklers

Sprinklers require less land formation due to their slower application rate than water infiltration. Sprinklers need pressurised water from a pump or an elevated reservoir to work. More expensive pumps and pipelines are needed here. It’s more efficient than surface irrigation, so open-minded farmers should consider it.

Drip-irrigation

Drip irrigation is the most advanced method. Options abound. They are made of thin plastic pipes with tiny holes along their length (30 centimetres to 1 metre apart). Pre-calculated drip rates irrigate one or two plants at a time.

Drip irrigation systems can save up to 30% of water. Farmers who can afford drip irrigation should use it. Small businesses can learn and grow using this method.

Frequency, amount of irrigation

Crop watering

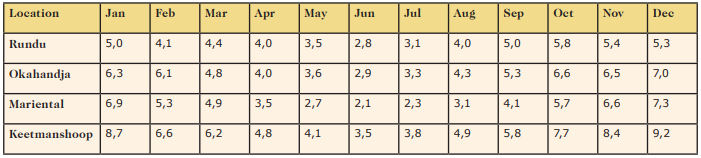

A plant’s water needs depend on its type, age, temperature, humidity, sunlight, and wind speed. The depth of water in millimetres per day includes plant use and soil evaporation. Using climate records, you can estimate crop water use.

However, consider the following:

- When it’s hot, windy, or dry, crops need more water.

- Humid or foggy weather reduces crop water use.

- Young plants need half as much water as mature ones.

You can calculate a field’s water needs using this formula:

(L) = (mm) x (m²)

For example, in March, a 10-by-5-meter tomato field near Rundu needs 4.4 mm per day, or 220 litres.

Overestimating water use from the above figures is recommended. This can make it difficult to determine “normal” weather and cause irrigation water to leak or be applied ineffectively.

Irrigation frequency

A plant’s roots can only thrive with water and air. If the topsoil is always wet, plants prefer to extend their roots horizontally rather than deep. Topsoil is dry, so roots grow deeper.

Table 1 shows the average daily water use for vegetables in Namibia.

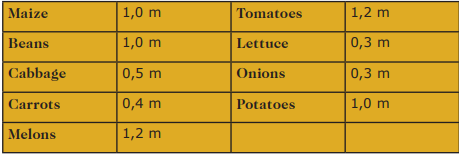

Deep roots help vegetables draw water from deeper soil layers.

Table 2 shows the optimal crop root depths.

Crops grown in good, deep soil that does establish fine roots will likely receive too much water.

The “sausage test” determines if a plant needs watering. Dig deep. Squeeze some dirt from the hole’s bottom to improve your grip. When squeezed, moist soil forms a sausage-like mass and doesn’t need watering (see illustration). If the soil crumbles, water it. Dig another hole after watering to make sure the plants get enough water.

Test-sausage (Image source: infonet-biovision.org)

To avoid evaporation losses, water will be pumped into deeper soil layers once a week. Deep soil loses little water.

Deep watering allows the topsoil to dry between irrigations, delaying insect reproduction. Seedlings need daily irrigation.

When to irrigate

Morning or night is best for watering. Two options exist:

- Even the smallest drops can linger on wet leaves for hours. These drips can intensify the sun’s rays and damage leaves in bright sunlight. Very common on cabbage plants.

- Midday is peak evaporation, so more water applied then will evaporate. Total plant watering increases wet surface area and evaporative loss. Tomato leaves can be cooled with water during the day’s hottest hours.

Source:

The Namibia Agricultural Union and the Namibia National Farmers Union, 2008 Crop Production Manual.