Erosion is caused when a lot of water runs over bare soil. Soil usually becomes bare because of overgrazing, which is caused when a farmer keeps more livestock than the land can support. If the farmer has no other land where the animals can graze, the vegetation doesn’t get a chance to recover, even after it has rained.

During a drought, the situation gets worse. The bare soil is baked hard by the hot sun and whatever plants remained, also shrivel up and die.

When a heavy downpour of rain follows, there are no plants to protect the soil and to keep the running water from washing away the soil.

Flat land without any vegetation.

Water that flows unchecked over the soil causes soil erosion. Eventually, most of the topsoil is washed away and the subsoil is all that is left, without any organic material or nutrients for plant growth.

Even if some water remains on top of the bare soil, little or no moisture penetrates the hard soil. Because there are no plants on top of the ground, there are also no roots underneath the ground that will hold the moisture, and muddy puddles soon evaporate leaving the land as dry as before the rain.

To prevent this from happening, Ken Coetzee and Wallie Stroebel of Conservation Management Services from George in the Western Cape were appointed by Wells for Zoe, an Irish charty organisation, to help restore some of the degraded lands in Malawi.

Wells for Zoe is working on the Enyazini reforestation project near the town of Mzuzu in the northern part of Malawi. They provide wells and pumps for the community in this area, and they are busy with the reforestation of the mountain slopes that were stripped bare by the cutting down of trees for firewood and charcoal. For this purpose, they have set up a nursery where indigenous trees are grown in large numbers.

Example of flat, bare land with little vegetation.

In the previous two issues, we discussed how soil erosion on steep slopes, which had caused head-cuts and gullies, was successfully treated by using available plant material such as branches, grass, and shrubs. This readily available material was used to build branch breaks and grass fences that were used to slow down the water and prevent more damage.

In this issue we look at the way in which Conservation Management Services helped to prevent the soil from drying out by making hollows, or ponds, to capture the run-off rainwater, silt, animal droppings and seeds.

Action

On bare areas capped with hard soil, hollows are created to allow water to infiltrate and rehydrate the parched soil. Hollows or ponds are constructed to catch the water before it runs off, thereby creating a place where run-off soil or silt is captured, as well as seeds and other organic material. When the seeds germinate, grass and other plants grow to provide ground cover for the bare soil.

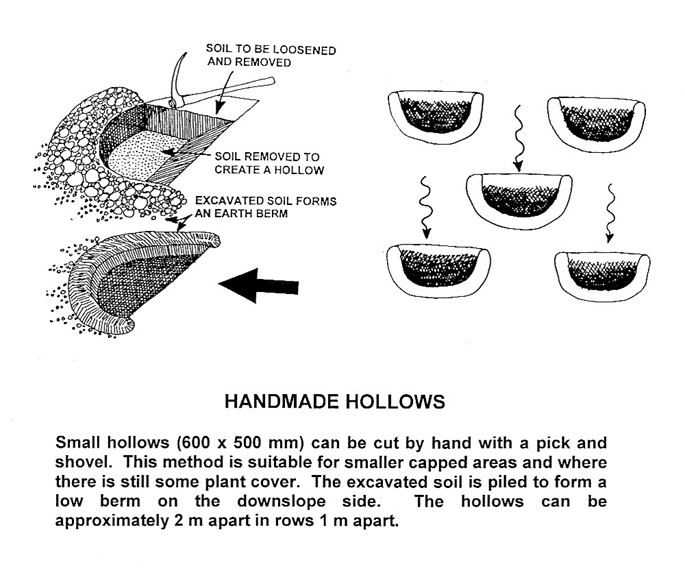

Figure 1: The construction and layout of hollows or ponding.

This method consists of digging rows of hollows across flat bare areas where little or no plant cover exists. It is applied on flat or gently sloping ground, and each hollow incorporates an inflow and an earth berm opposite the inflow, creating a small dam which can hold roughly 45 to 55 litres of water.

Step-by-step action

On bare, flat areas of land where plant cover is absent, mark the outline of the hollows in alternating rows. Avoid the destruction of existing plants, as they help to bind the soil.

Hollows should be about two metres apart in rows of one metre apart. The hollows should be cut in a horseshoe shape (see Figure 1). Arrange the rows of hollows so that water flowing past the hollows in one row will be trapped in the hollows of the next row, in other words, stagger the rows of hollows across the site to be treated.

- Digging the hollows by hand.

- Compact a soil berm on the downslope side of the hollow to ensure that it will be strong enough to hold the run-off water.

- Put leafy branches or brush inside the hollows to create a microclimate for plant germination and to protect new seedlings from grazing animals.

- The final product with hollows staggered across the land.

The layout should be staggered (See the photo of the final result).

It is very important that the open side of the horseshoe faces in the direction that the water will be flowing from. This will ensure that the maximum quantity of water is captured and held.

Dig the bowl of the hollow by using a hoe or pick and shovel and place the excavated soil on the bottom side of the hollow to create a berm or little dam wall on the side to which the water will normally flow. Make sure the berm is compacted throughout the process to ensure that it will form a strong retaining wall.

The hollows need to be no larger than 800 mm wide, 500 mm wide and 300 mm deep.

Place brush or mulch inside every hollow to create a favourable environment for seed germination and to protect the seedlings.

Sow a mixture of local grass seeds in every hollow to ensure that new plant cover will be established. The wind will also help to bring grass seeds into the hollows; in grassy areas seeding will not be necessary.

Contact details:

Ken Coetzee, Wallie Stroebel and Bruce Taplin

4 Chestnut Street, Heather Park, George, 6529, South Africa

Cell Ken: +27 76-227-5056; Wallie +27 82-493-1441

Website: www.conservationmanagementservices.co.za