The term redwater (babesiosis) is a generic term that refers to two diseases, namely African redwater and Asiatic or European redwater. In cattle, it is caused by a protozoan blood parasite in the red blood cells.

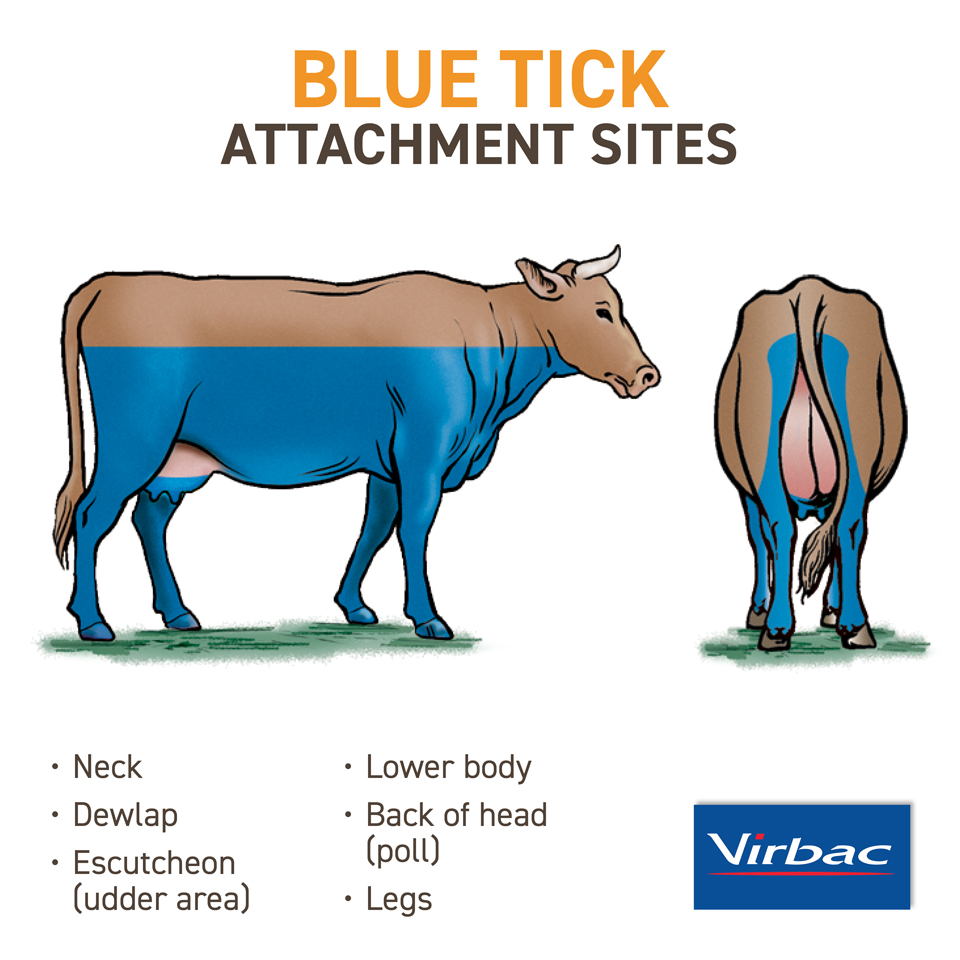

Two species of the blood parasite occur in Southern Africa, namely Babesia bigemina, which causes African redwater, and Babesia bovis, which causes Asiatic and European redwater. African redwater is transmitted through the bite of two species of blue tick, namely African blue tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) decoloratus, and the Asiatic blue tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus, which are both single host ticks.

The red-legged tick Rhipicephalus evertsi evertsi can also transmit the parasite, but its role in transmission is limited. In Zimbabwe, B. bigemina occurs throughout the country together with its main vector, Boophilus decoloratus. The distribution of B. bovis follows closely that of its vector Boophilus microplus, which is limited to the eastern part of the country. Cattle infected with the parasites remain carriers for considerable periods and they have long-term immunity against redwater. Animals that have recovered from African redwater have some immunity against Asiatic or European redwater, but not the other way round. To protect cattle against serious disease and mortalities caused by the redwater parasite, less virulent vaccine strains of the parasite in the form of live blood vaccines are used to immunise cattle against both types of the disease.

Figure 2: Lifecycle of a blue tick. (Source: Virbac).

Transmission

Redwater is only transmitted by these carrier ticks, also called vectors, which are infected with the disease when feeding on an infected or carrier animal. African redwater, is transmitted from the larval stage via the nymph stage to the adult tick. Infected female ticks that drop off the host animal carry the disease. They lay eggs in the soil and the disease is carried to the larvae in a process called transovarian transmission.

The nymphs and adults of the next generation transmit the disease to susceptible host animals. In Asiatic or European redwater, the course of the disease is similar. The infected female also transmits the disease transoviarially to her progeny, although only the larvae stage of the tick transmits the disease to cattle. Although the larvae no longer carry the disease after transmitting it, the next generation of nymphs is again infected by feeding on a carrier bovine, which once more transmits the disease to adult ticks.

Where an area is normally free of redwater, climatic conditions that are favourable for the survival of the ticks can lead to an outbreak should the ticks enter the area when infected cattle are introduced.

Male vs female blue ticks. (Source: Virbac).

Resistance and immunity

All cattle breeds can get infected, but indigenous breeds such as Zebu and Sanga are more resistant than European breeds. Most animals develop long-term immunity, which may last life-long, after a single exposure to redwater. Redwater often occurs in hot summer and autumn months, which corresponds with the increase in the number of ticks.

Calf vulnerability

Calves younger than two months that have been born from dams that have not been exposed to the redwater parasite and have no immunity against it, are susceptible to infection. Calves born to cows that are immune to redwater are protected through colostrum immunity, also called passive immunity, until the age of about two months. Until about six months, the calves have non-specific immunity, and although it decreases, calves up to nine months seldom show symptoms or only develop a mild form of the disease. This immunity is not absolute and a calf with a less effective immune system after suffering from some diseases, is malnourished, or suffering a high parasite load, can be susceptible to redwater.

Even older animals that have been exposed to the disease and have become immune to it, can be susceptible under high-stress conditions. The cow’s resistance against disease can diminish around calving time and she can get redwater, which is more serious and can lead to death in adult animals that get it for the first time. Where enough ticks occur, all calves should become infected at about nine months of age, which provides it with a natural immunity and usually no outbreaks occur in such an area. Where there are too few ticks, either

because of natural factors like drought, or due to tick control like a dipping regime, calves are susceptible to redwater should an outbreak occur. Immunisation against redwater is usually used to supplement natural infection to protect animals that have not become infected as calves, to prevent them from a serious infection later. When cattle in a redwater area are moved from one camp to another, or to another farm, there may be an outbreak. They can be treated by preventative injections of imidocarb or diminazene according to prescription to protect them against an infection. Consult a veterinarian or extension officer for more information.

Symptoms

Symptoms occur two to three weeks after being bitten by a tick. A high fever (40,5> °C) may occur, as well as light to dark red urine, anaemia and sometimes jaundice, as well as a lack of appetite or depression. The name of the disease is derived from the red urine, and the jaundice may lead to a wrong diagnosis of the condition as gallsickness. The disease develops quickly, and the animal may die if not treated quickly. A high fever may be present for a few days before the other symptoms appear, including more vague symptoms like reluctance to move, a dry nose, dull hair coat and diarrhoea.

The urine is also not always red. When the disease is in an advanced stage, the animal may show nervous symptoms caused by the increased parasites in the blood vessels of the brain, increased or reduced reaction to stimuli, poor condition, muscular tremors, or convulsions and even coma. This is called cerebral redwater, which can be confused with heartwater. The animal may go into shock due to the high number of parasites in the superficial blood vessels, which may lead to an oxygen shortage in the organs, organ failure and death. Redwater is, after all, believed to be the greatest cause of cattle mortality in Southern Africa.

Diagnosis

Consult a veterinarian, who will do a provisional diagnosis with a blood or brain smear or confirm it with a postmortem.

Treatment

Sick animals must not be stressed. Protect them from bad weather and provide fodder and clean water. Treat the animal as soon as possible with diminazene and imidocarb according to the dosage instruction, as less may cause resistance to the medicine, while an overdose can be toxic. Imidocarb has been reported to protect animals from disease, but immunity can develop and there are concerns about residues in milk and meat.

Mild cases may recover without treatment, and treatment with drugs is most likely to be successful if the disease is diagnosed early, but once the animal has developed anaemia, it may be too late. In some cases, where a valuable animal is infected, blood transfusions and other supportive therapy could be considered.

Control

Redwater can be controlled by keeping cattle free of ticks, but resistance to acaricides (pesticides that kill ticks and mites) has increased in tick populations with time, making them ineffective. The aim is to maintain a balance of tick exposure that enables the development of natural immunity, and to ensure that cattle are not negatively affected by ticks. In redwater-endemic areas, cattle must adapt to the conditions, and the ideal is to strive for endemic stability. Inoculating animals with blood vaccines provides good protection and is recommended.

The blood vaccine is provided in frozen form. Consult a veterinarian or extension officer for the correct procedure and dosage. Reaction to redwater vaccination usually develops between one and three weeks after inoculation or infection, with African redwater symptoms appearing within seven days, and Asiatic redwater symptoms appearing 10 to 12 days after infection.

Prevention

Effective control of tick fevers can be achieved by a combination of measures directed at both the disease and the tick vector. Tick control by acaracide dipping every four to six weeks can be done in heavily infested areas. Because of resistance of ticks, chemical residues in cattle and environmental concerns over the use of insecticides, vaccines are readily available and are highly effective. Vaccinated cattle must be kept clean of ticks for six weeks.

For more information, read more on the website for the Zimbabwe Veterinary Services at http://www.dlvs.gov.zw/

Source references

Bovine Babesiosis (Redwater, Tick Fever) (2022) The Cattle Site https:// www.thecattlesite.com/diseaseinfo/196/bovine-babesiosis-redwatertick-fever

Du Preez, J., Malan, F. (2015) African and Asiatic redwater in cattle. Farmer’s Weekly https://www.farmersweekly.co.za/agri-technology/farming-for-tomorrow/african-and-asiatic-redwater-incattle/

Katsande, T.C., Moore, S.J., Bock, R.E., 2001) Factors influencing the prevalence of bovine babesiosis in Northern and Eastern Zimbabwe. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/zvj/article/view/5302

Norval, R. A., Fivaz, B. H., Lawrence, J. A., Daillecourt, T. (1983) Epidemiology of tick-borne diseases of cattle in Zimbabwe. I. Babesiosis DOI: 10.1007/BF02239802 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6868134/