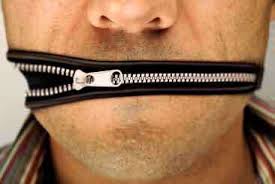

Communication is the key to success in maintaining a successful family agribusiness. Yet many families never get to first base in addressing in communication issues, even those who realise how important it is to the outcome of ensuring the sustainability of their businesses.

Why families don’t communicate

Hidden agendas are a major obstacle to communication in families. In some cases, the father’s hidden agenda may be that he has no intention of ever letting go. But the son’s failure to confront his father on the succession issue may result from a hidden agenda, too. It may be that he really doesn’t care for the responsibilities of leadership, but he doesn’t have the courage to say so.

A second block to communication results from waiting too long to address the issues. With the passage of time, small silences can grow into a mountain of guilt and rationalisation. On the one hand, the father may be thinking, “I should have dealt with this years ago, and I have let it go too long. Now I am too embarrassed to deal with it.” On the other hand, the son may be thinking, due to no word to the contrary from Dad, his entitlement to the top job grows with every passing day.

During my recent visit to AgriTech Expo in Chisamba, Zambia, I met a son, already in his 30s, who had invested many years of his life in the hope of eventually running the family agribusiness. However, his father, already well into his seventies, had no intention of letting go. It would be advisable for the son to communicate his desires to follow in his father’s footsteps to take over the management of the business.

Breaking down the wall of silence – a few rules to help improve communication:

The sun should never set on an emotionally significant issue within the family that remains unresolved. Avoid letting issues fester until they get too hot to handle.

Find the right time and place to talk seriously. Avoid the interruptions at work.

Before opening your mouth, clarify in your mind what you want and what is fair to other family members. Be sure about the principles you want to adhere to.

Seek objective advice on your own possible hidden agendas and on the best way to frame the issues. Once the issues are on the table, look for alternative win-win solutions that address both business and family needs and promise a way out of the dilemma.

Farmer overlooking the success of his crops

Family members should agree on what will be expected of successors-to-be and on measures to determine whether those expectations are being met. Potential successors should be given frequent feedback.

Before assigning blame for something, ask yourself what you may have contributed to the problem. Remember that only you have the power to change yourself.

Keep the discussions moving forward. Be willing to negotiate. Remember that other family members may not be ready to hear you. It may take years for them to unfreeze. Stick with it. Build goodwill through the process.

A third and critical block is the feeling that the issues are so highly emotional that they seem to preclude any rational discussion. When a son has invested 18 years of his life in the hope of eventually running a business, any talk of succession with his father is bound to be powerfully charged for both.

Real communication has an element of vulnerability to it. So, if the son goes to his dad and tells him about his concerns for the future, he may hear something he doesn’t want to hear. Yet it is far riskier to the relationship and to the son’s future to let issues fester.

Questions about the competence of children pose some of the greatest challenges to family communication. For a while, parents can rationalise away doubts about competence as “a maturity problem,” “an attitude problem” or “the influence of friends.” By the time children reach 30, however, parents should know whether their offspring have what it takes or not. If the parents don’t know, the children must be tested; they should be given more responsibility and the chance to fail. Parents must stop rescuing children. The children must be subject to serious evaluation by others – managers and personnel experts who can give them objective feedback. The next ten years are critical in a young adult’s life. Without good communication in the family, members of the next generation may hang on to illusions about their future in the business.

When crisis is imminent

The father and son in my example have a lot of work to do. Ten years ago, Dad probably could have eased his son out of the business without causing an uproar in the family. That would have made it possible to prepare a professional manager to run the company when the father was ready to retire. Now it is too late. The son has few career alternatives. Because Dad has not dealt with the issue for so long, he has lost a lot of his moral authority. He knows it and feels powerless.

The father must separate issues of authority on the business from the son’s need to save face. He must find a way of giving authority to those who are most able to provide competent leadership, while leaving his son with an adequate measure of self-esteem. Perhaps the son could be put in charge of a smaller entity, such as one of the farming operations. Or he could have a seat on the board, while professional non-family managers run the family agribusiness.

Both father and son must look for win-win alternatives that can extricate them from the dilemma that has led to mutual avoidance of the issues.

The situation demands an enormous amount of communication, patient problem solving and compassion. Sadly, such qualities are frequently beyond the emotional resources of some families. The leader then faces the awful choice of saving the business or the relationship.

Trevor Dickinson is the CEO of Family Legacies, a family business consulting company. For more information visit www.family-legacies.com