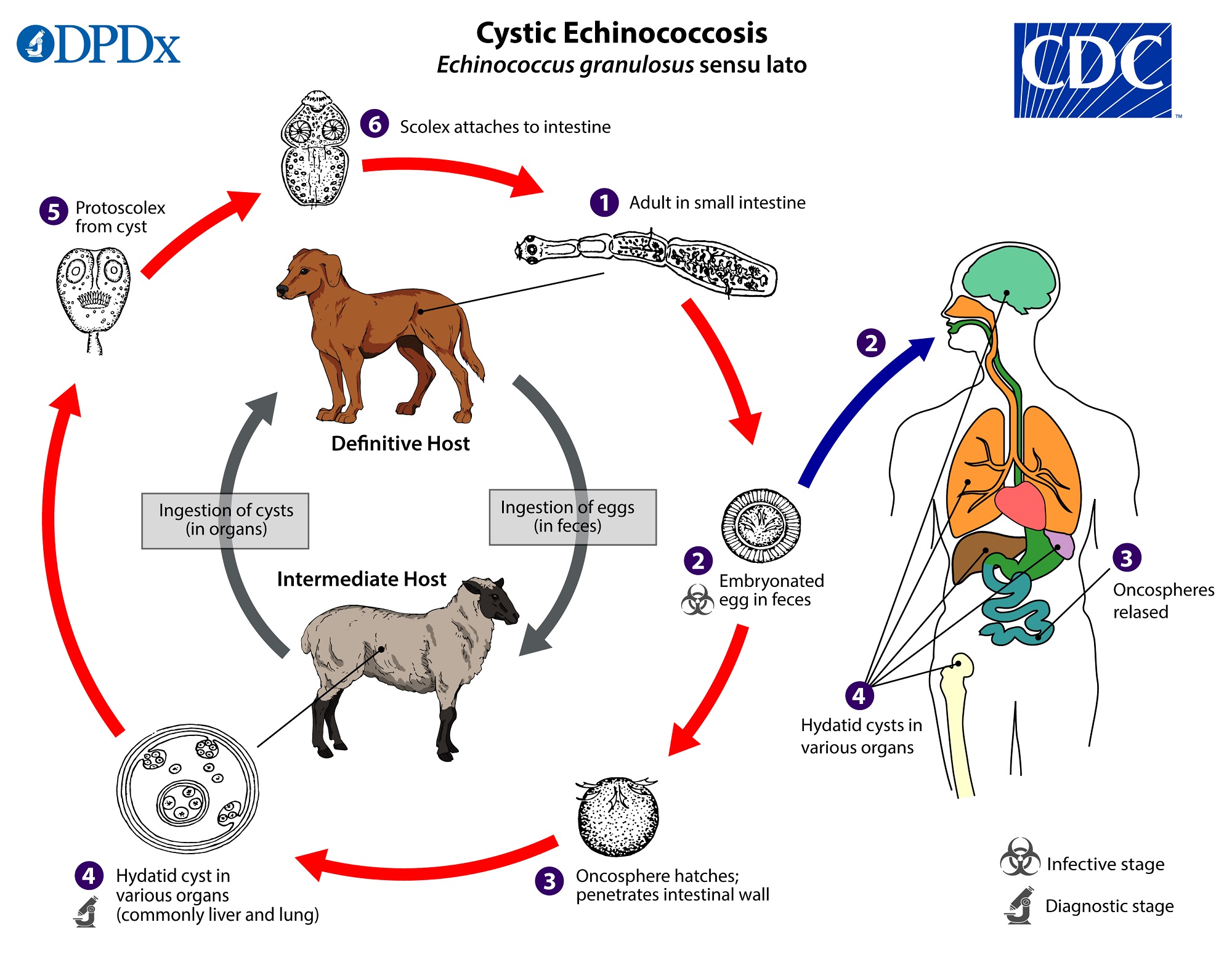

Echinococcus granulosus is a type of tapeworm which is a harmful parasite. It’s a zoonotic disease, which means it spreads from animals to people, with a life cycle involving humans, dogs, and ruminant livestock.

Tapeworms are flat, segmented worms that live in the intestines of some animals that become infected by grazing in pastures or drinking contaminated water. Humans can be infected when eating undercooked meat from infected animals and by inadvertently ingesting the eggs of the parasite while handling animals, including domestic dogs.

Tapeworm occurs practically worldwide, and more frequently in rural, grazing areas where dogs ingest organs from infected animals.

In Africa, it occurs in ungulates, including cattle, sheep, goats, and camels, which are the intermediate hosts, while the natural definitive hosts are wild and domestic dogs. As a zoonotic disease, it can also infect humans and more than one million people are believed to be affected at any one time.

The tapeworm lifecycle: Echinococcus granulosus is a zoonotic disease, which means it spreads from animals to people, with a life cycle involving humans, dogs, and ruminant livestock. (Source: Pixabay)

Endemic regions

In northwestern Kenya and Maasai land, the disease has long been endemic, meaning that it has been present at a low level over a long period in pastoralist communities that live and work closely with livestock.

Traditional livestock farming in Kenya’s north, for example in Turkana, has concentrated the risk of disease in communities there. However, as a result of growing population numbers and thus a demand for meat, it is spreading south as animals are driven there for slaughter, bringing tapeworm infections with them.

The human factor

Humans are infected through ingestion of parasite eggs in contaminated food, water, or soil, or after direct contact with animal hosts.

The two most important forms in humans are cystic echinococcosis or hydatidosis, and alveolar echinococcosis. This article focuses on cystic echinococcosis.

The parasite can grow slowly in people for years to form thick-walled cysts in vital organs, such as the liver and lungs. It can cause abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. If not treated, it can be fatal.

Treatment of tapeworms is expensive and complicated and may require extensive surgery and/or prolonged drug therapy.

Preventive measures include deworming dogs, slaughterhouse hygiene, and public education regarding hygiene.

A dog eats an Echinococcus cyst at a slaughterhouse. (Source: ZED Group, Liverpool/ILRI)

Follow these rules:

- Prevent contamination by cooking meat thoroughly

- Freezing for at least 24 hours destroys tapeworm eggs;

- When travelling in developing countries, cook vegetables with uncontaminated water before eating;

- Wash hands with soap and hot water before preparing or eating food.

Study in non-endemic regions

A recent study in collaboration between the International Livestock Research Institute, Jomo Kenyatta University of Science and Technology, the University of Liverpool and the Kenya Medical Research Institute, tracked the spread of this tapeworm into populations where the disease is not endemic.

The researchers conducted four pieces of research which covered how prevalent Echinococcus tapeworm was in livestock being brought for slaughter, how it spread to people and how great the human disease burden was.

It was found that the parasite is highly prevalent in livestock moving into non-endemic areas and is now spreading via dogs, to establish a life cycle involving human populations. The findings highlight how important it is to carry out disease surveillance, particularly as populations grow and dynamics change.

With infected livestock from endemic tapeworm regions and dogs scavenging for discarded animal by-products, conditions can be created where it is likely that more humans can be infected. (Source: Pixabay)

Presence in livestock

The study was done in the bordering counties of Busia and Bungoma which previously didn’t have tapeworm disease, or cystic echinococcosis, among humans and livestock.

The first study assessed how prevalent tapeworm was in livestock being brought for slaughter. Over two years, the research team collected over 16,000 reports in both counties and found a very high infection rate in these samples, namely 32% of the livers of cattle and goats, 74% of lungs in cattle and 58% of lungs in goats.

The parasite has been introduced and is spreading slowly in groups of people and dogs that have not been exposed before. (Source: Pixabay)

Dogs as vector or carrier

The second and third studies sought to understand how the tapeworm might spread to humans in these counties. It was found that dogs gathering at slaughter facilities ate whatever was discarded, including the lungs that were discarded because they contained cysts. Dogs could get tapeworms from eating meat like this.

The movements of more than 70 dogs regularly visiting the slaughterhouses were tracked with GPS collars for five days each. The parasite was present in the faecal samples of which 16% were positive for Echinococcus antigens, which meant these dogs could bring the disease into households and people living there.

The parasite matures in the dogs’ intestines and the dog sheds eggs in faeces, contaminating the environment. People get infected when parasite eggs from the environment are ingested, usually due to poor household hygiene.

The fourth study examined how great the human disease burden was in Bungoma County. By using ultrasound technology, cystic lesions which may indicate Echinococcus infection were found among a small number of around 1% of the community members.

Danger to humans

Although the population did not suffer extensively from the disease, early signs of the establishment of a local transmission cycle were determined. This means that the parasite has been introduced and is spreading slowly in groups of people and dogs that have not been exposed before.

This slow-moving outbreak could soon represent a much more significant public health problem if left unchecked. Ultrasound imaging could help monitor treatment and surgical outcomes, but many health facilities in the country don’t have the equipment. By the time human infections are advanced, expensive operations to remove these cysts are the only treatment available.

The Echinococcus granulosus infections often show no symptoms before the cysts grow large enough to cause symptoms in the affected organs. The rate at which symptoms appear depends on the location of the cyst in the organs. Cysts in the liver and lungs are most common, but other organs, including the spleen, kidneys, heart, bone, and central nervous system including the brain and eyes, can be infected.

If the cysts rupture, it can produce fever, skin rash or even anaphylactic shock; rupture of the cyst may also lead to it spreading.

The research team collected over 16 000 reports in two counties and found a very high infection rate in these samples, namely 32% of the livers of cattle and goats, 74% of lungs in cattle and 58% of lungs in goats. (Source: Pixabay)

A public health risk

Where infected livestock from endemic tapeworm regions and dogs scavenging for discarded animal by-products are found, conditions can be created where it is likely that more humans can be infected.

This is especially true where agricultural systems in Africa face increasing demands from population growth, as well as demographic changes such as population size, composition, and distribution. Rapid unplanned growth can have devastating unintended consequences.

Traditional livestock farming in Kenya’s north, for example in Turkana, has concentrated the risk of disease in communities there. (Source: Pixabay)

Neglected disease

The World Health Organisation (WHO) regards this disease as a neglected disease that needs more attention because it can be dangerous and invasive, and treatment is expensive. To protect populations, systems of surveillance must keep up with the changing world.

Tracking the spread of disease in a non-endemic region is an essential step to prevent future outbreaks of public health concern.

Sources

Dunkin, M. A. (2021) Tapeworms in humans. WebMD https://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/tapeworms-in-humans

Echinococcosis. (2019) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/echinococcosis/index.html

Lifecycle of cystic Echinococcosis, https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/echinococcosis/modules/Echinococcus_gran_LifeCycle_lg.jpg

Macpherson, C. N. L., French, C. M., Stevenson, P., Karstad, L., Arundel, J. H. (1985) Hydatid disease in the Turkana District of Kenya, IV., Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology, 79:1, 51-61, DOI: 10.1080/00034983.1985.11811888 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00034983.1985.11811888

Mutwiri, T., Fevre, E., Falzon, L. (2023) Tapeworm is spreading in Kenya – demand for meat brings parasite to new areas. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/tapeworm-is-spreading-in-kenya-demand-for-meat-brings-parasite-to-new-areas-209155?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Latest%20from%20The%20Conversation%20for%20October%2018%202023%20-%202770628020&utm_content=Latest%20from%20The%20Conversation%20for%20October%2018%202023%20-%202770628020+CID_6faf58ea88b3558c0f1de596ad71e92d&utm_source=campaign_monitor_africa&utm_term=Tapeworm%20is%20spreading%20in%20Kenya%20%20demand%20for%20meat%20brings%20parasite%20to%20new%20areas