Coccidia are unicellular, microscopic parasites, responsible for the disease called coccidiosis. When the parasite invades the intestinal walls and multiplies inside its cells, it could produce diarrhoea, an increase in mortality, and a variable negative effect on intestinal function, growth, and feed conversion.

Coccidia affecting poultry are from the genus Eimeria. In broilers, there are three important species, namely Eimeria acervulina (EA), Eimeria maxima (EM), and Eimeria tenella (ET). Frequently, birds are affected by more than one species at a given time.

The symptoms and effects on productivity depend on the cocci species affecting the flock, the immunity level of the birds, as well as on the severity of the infestation. In some cases, symptoms are clear and typical, resulting many times in important losses due to mortalities and reduced performance.

However, most cases are subclinical, which means that chickens do not present overt symptoms or a high mortality rate. Instead, the efficiency in production is greatly affected. This situation is further impaired if secondary conditions, such as necrotic enteritis, set in after the damage to the gut wall produced by the coccidia multiplication.

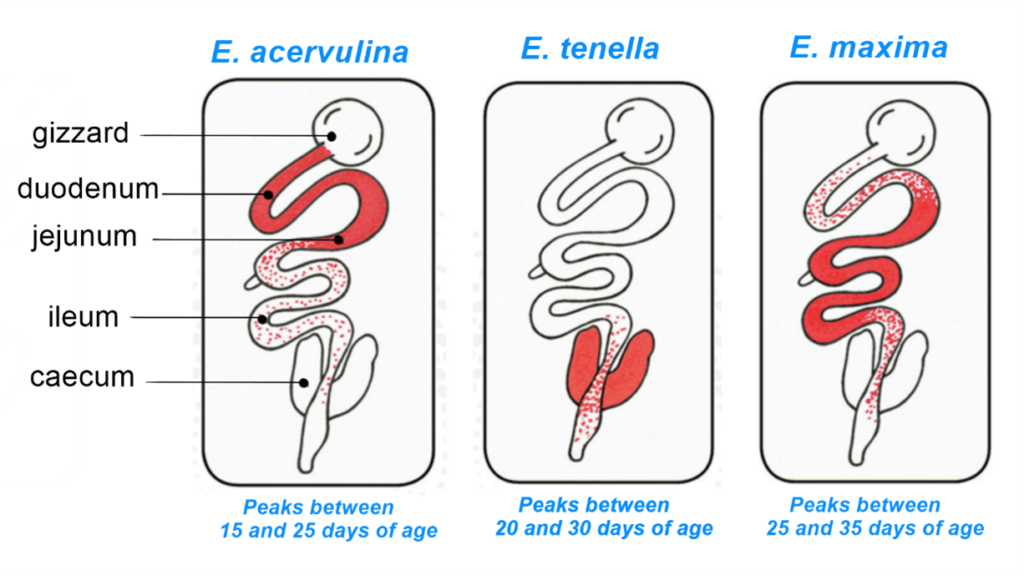

Figure 2: Distribution of the 3 main species of coccidia in the gastrointestinal tract of a chicken. Note the different ages at which they peak.

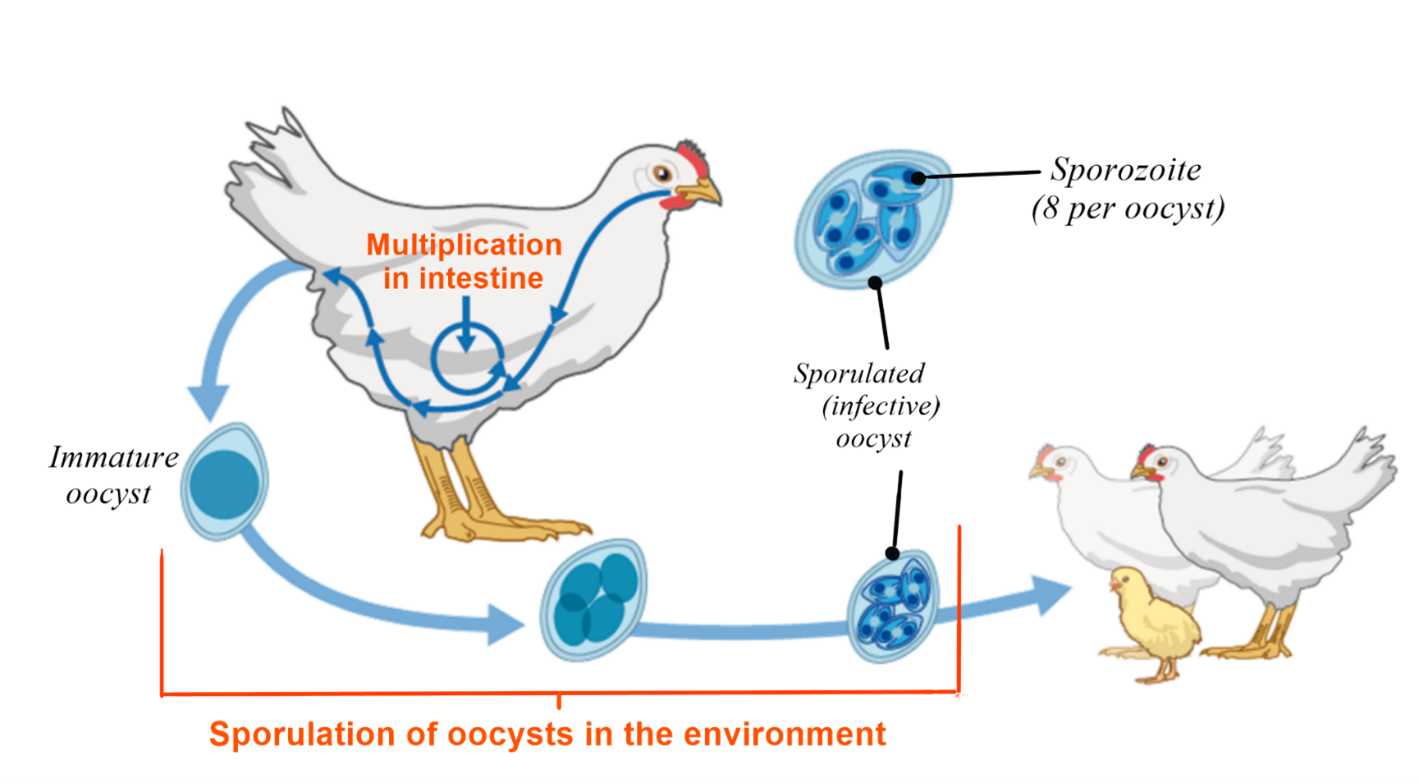

The cycle of cocci and the importance of the environment

Coccidia go through a replication cycle consisting of many stages, some of them occurring inside the bird and some outside. The only stage capable of infecting a bird is the sporulated oocyst, which looks like a microscopic balloon inside which there are eight infective cells; each one of these cells is called a sporozoite (Figure 1). When a sporulated oocyst is ingested by a chicken, it is broken down in the gizzard, and the sporozoites are released. Then, the sporozoites invade the cells of the epithelium lining of the intestinal wall and start multiplying. After two or three multiplication cycles, new oocysts are produced and released to the environment in the faeces (Figure 1).

When oocysts are excreted, they are still immature and unable to infect. For them to become infective, the content of the oocyst should divide into the eight sporozoites we mentioned above, in a process called sporulation (Figure 1). The oocyst will undergo sporulation only if in the environment has enough moisture and the temperature is between 21 and 32 °C. This is the reason why coccidiosis is more common during the rainy season, or when the litter becomes wet (for example due to spillages from the water source).

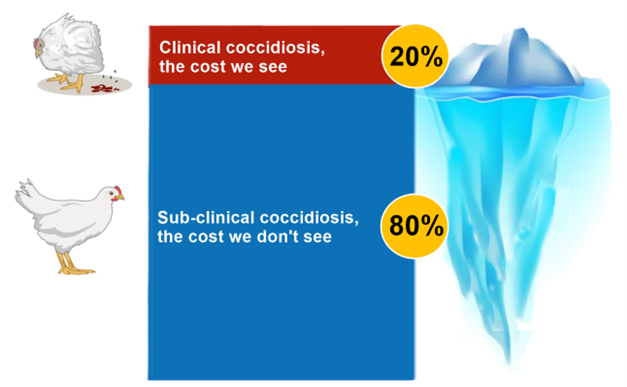

Figure 3: Analogous to the largest, hidden portion of an iceberg, the major proportion of cases of coccidiosis are sub-clinical and unnoticed.

How do different cocci strains affect broilers?

Eimeria acervulina (EA)

EA is the species that appears first. It affects the anterior section of the intestine, mainly the duodenum. In the first stages of infestation, the walls of the intestine show short transversal white lines, which begin to grow and join to each other as the problem progresses (Figure 2).

Moderate to severe cases usually result in diarrhoea, problems of digestion and absorption, and poor performance. Mortality is normally low to moderate.

Eimeria tenella (ET)

ET appears after EA, affecting mainly the caeca (Figure 2). It starts as small haemorrhages in the wall of the caeca. It progresses with thickening of the caecal walls and increase in haemorrhages, until the caeca are distended with blood and clots. When birds reach this stage, death follows soon after.

Although the lesions and symptoms are alarming, the effect in productivity is usually lower than for the other two strains. The reason for this is twofold. Firstly, since not much digestion/absorption takes place in the caeca, the effect on efficiency of feed utilisation is not so important. Secondly, since blood-tinged faeces appear soon in the disease, farmers normally act much earlier with this species.

Eimeria maxima (EM)

EM is, the largest of the three cocci species, appears later than EA and ET, and produces the most damage. It affects the middle small intestine (the jejunum), where most of the digestion and absorption take place (Figure 2). Therefore, EM has the potential of seriously affecting the performance of the flock, even in the early stages of the disease.

Soon after infection, the multiplication in the wall produces small areas of haemorrhages that are observed as red pinpoint dots on the outside and inside surfaces of the intestine. In some cases, the lesions are so small that they are very difficult to identify with the naked eye; the veterinarian needs to observe intestinal scrapings under the microscope to be able rule out a mild early infection. However, as the disease progresses, the wall of the intestine thickens, there is a significant increase in intestinal mucus, the intestine becomes severely distended, and haemorrhages increase in severity.

The issue of subclinical coccidiosis

Subclinical coccidiosis is much more frequent than one may think. It is estimated that of the total cases of coccidiosis, only 20% are clinical, the balance being subclinical. If this was represented as an iceberg, the visible tip would account for the proportion of infections with clear signs, whilst the subclinical ones would be depicted by the biggest, hidden, underwater mass of ice (Figure 3).

This doesn’t mean that subclinical cases do not have an economical impact. On the contrary, they are responsible for the biggest losses due to coccidiosis. Mild levels of infection can already have a negative impact on digestion and absorption, resulting in high feed conversion ratios, delayed achievement of target body weights, and poor uniformity.

Therefore, a flock affected by coccidiosis does not necessarily show blood-tinged faeces and high mortality; most times you will only see that the broiler flock is not performing as expected.

How to prevent coccidiosis in my broiler farm?

In future articles we shall further analyse the control of the disease. This time we shall briefly discuss two extremely relevant factors of coccidiosis control, namely the management of the environment and the utilisation of coccidiostats.

As mentioned above, environmental conditions play a fundamental role in the sporulation of the immature oocysts. Such oocysts will only become infective if they are exposed to high humidity, warm temperatures, and ideal levels of oxygen.

Therefore, avoiding the formation of wet litter patches under the water sources and next to the windows on rainy days, as well as removing damp/wet bedding material, are essential measures to reduce the prevalence of coccidiosis. Using bedding material that absorbs water more efficiently (for example wood shavings instead of straw) is desired. Finally, proper cleaning and disinfection of the house after cropping the flock, as well as implementing an appropriately long down period between flocks, may also be beneficial.

Coccidiostats are drugs added to the broiler feed with the objective of stopping the multiplication of coccidia in the bird’s intestine. These drugs are routinely used in commercial diets; all reputable feed mills are currently implementing coccidiostat programmes.

One of the main premises to consider is not to use a given coccidiostat for prolonged periods to avoid the development of coccidia strains resistant to its active ingredient. Many times, this resistance can also apply to drugs that are similar in structure. The best option is to rotate products at least every four to six months (some products can only be used for one cycle every 18 months), making sure to alternate drugs of different chemical structure. We shall discuss different rotation options in an upcoming article.

As usual, remember to consult your veterinarian whenever you observe issues of low performance. He/she will be able to diagnose the problem and prescribe a treatment and establish suitable control programmes.